Black Voices: Candice Wicks-Davis on Home, Healing, and the Labor of Reclamation

As Black Spaces: Reclaim & Remain moves into its final weeks of its run, we’re highlighting a conversation with an important community member whose life and practice resonate with the exhibition’s themes. This dialogue is one that invites readers to reflect on how Black communities across generations have created, protected, and reimagined spaces of belonging, even in the face of displacement and erasure.

In this piece, we spoke with Candice Wicks-Davis (also known as Candice Antique), whose work as a singer, educator, facilitator, and cultural organizer has long centered the healing and empowerment of Black communities. Whether she is leading freedom songs, co-producing community gatherings, or teaching decolonial frameworks, Candice brings forward a vision rooted in love, collectivism, and cultural memory. Her reflections echo many of the questions at the heart of the exhibition.

Candice begins by grounding her story in place.

“I was born and raised in Long Beach, California, and still feel a deep sense of connection and love for it and will always rep my city! But I always felt like a “black sheep”—my perspectives, style, and values were always seen as “radical.” When I moved to Oakland nearly 30 years ago to attend UC Berkeley, it felt like I had found my tribe. I fell in love with the spirit of activism, the culture, the arts, and the people.”

Her words reflect a familiar story within Black migration histories: home is not only where one comes from, but where one is fully seen. Throughout her life, Candice has been deeply involved in reclaiming and sustaining Black spaces across the Bay Area.

“As a student, I organized to keep Affirmative Action in the UC system… For 15 years, I also co-produced the Life is Living Festival in West Oakland, which affirms and carves out space for the Black community to gather, build, and heal annually. I co-hosted and co-produced the Black Love Brunch for 4 years in Oakland with my husband to honor Black partnership and marriage. I produced ‘Mr. Davis’ Classroom’ which is a Black history lecture series that my husband teaches several times a year. Lastly, I am the Treasurer and Board Member of Young, Gifted and Black, a youth performance ensemble to teach Black children resilience and pride.”

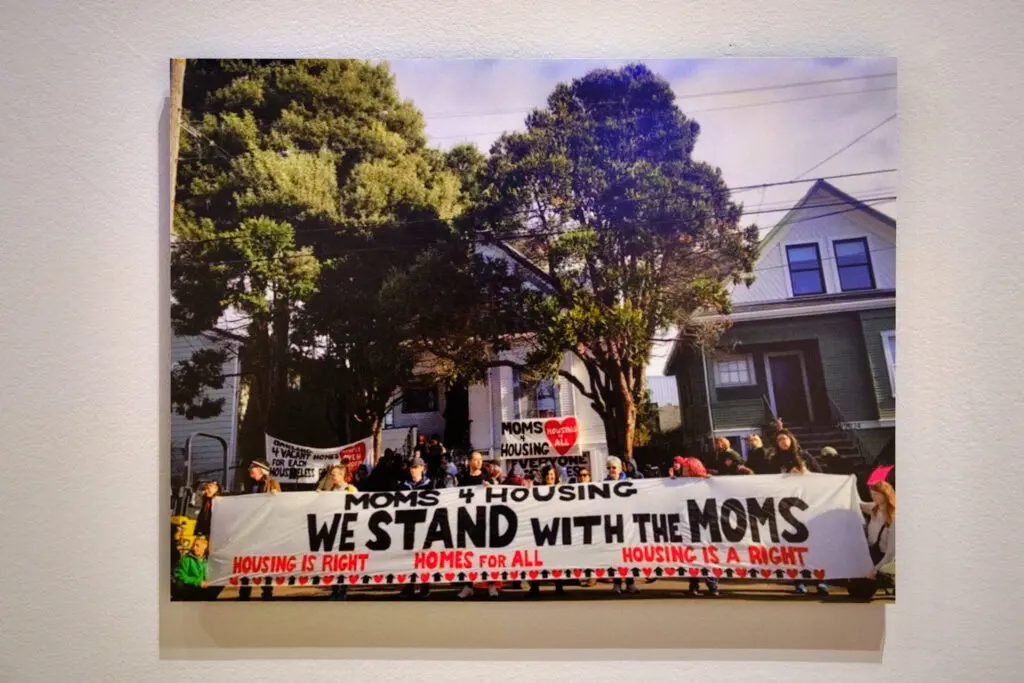

These efforts reflect the heart of Black Spaces: that Black homeplaces—whether festivals, classrooms, or community institutions—are built and protected through collective labor.

When reflecting on the role of art, storytelling, and architecture in building a more equitable future, Candice points to culture as the spark for social transformation.

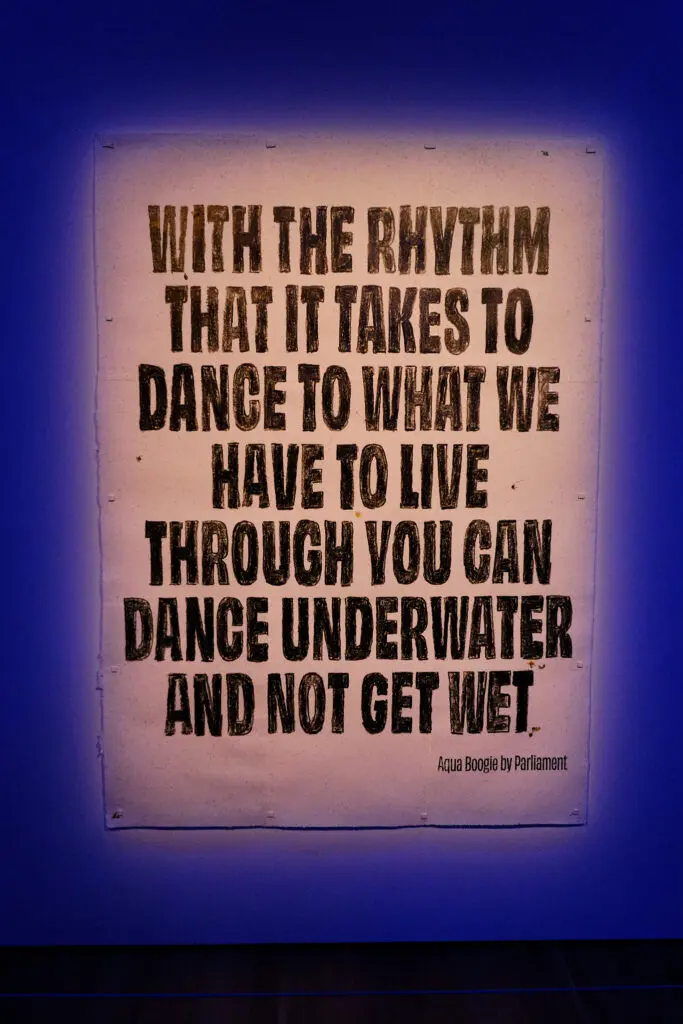

“Art and storytelling are essential, because culture is often the precursor to social change. When you look at the art during the time of the Civil Rights Movement or Black Power Movement, it led a generation of young people of all races to protest racist policies and treatment, the war in Vietnam, and to fight for women’s rights. Once the power of art—particularly music—was figured out, it was co-opted and used to undermine the movement. We must always make art that affirms Blackness, resistance, and life. It is timeless and even if it doesn’t become commercially successful, it can be a blueprint or inspiration for the generations to come.”

Her perspective resonates with the contemporary installations featured in the exhibition, each of which imagines future Black spatial possibilities through visual culture, design, and archival practice.

Candice also speaks to the importance of memory—particularly in moments of political struggle.

“Your rights should never, ever be taken for granted. A right, once won, must be maintained and monitored to ensure that no one is chipping away at it. Democracy requires participation. Make it a practice to know and honor our ancestors’ contributions to the struggle for liberation. They will give you the wisdom and strength you need to protect your rights. Don’t let the powers that be erase your memory.”

This call to remembrance echoes through the histories of Russell City and West Oakland, where community members continue to fight not only for justice, but for their stories to be protected and passed on.

On healing, Candice emphasizes repair at the personal, familial, and communal levels.

“Each individual Black person must confront the white supremacy embedded in their psychology and decolonize. The family must be healed. We have to forgive our parents, grandparents, etc. They did the best they could, considering that some of them were one generation removed from slavery. We have to break the unhealthy patterns that we learned from our enslavement, the war on drugs, mass incarceration, etc. We must build community. We cannot allow individualism to govern our community…. Collective care and mutual aid is how we survived the worst of times. Lastly, we build institutions for and by Black people, and we work in solidarity with other oppressed groups.”

Her vision aligns closely with the exhibition’s commitment to honoring both harm and restoration, and to uplifting the strategies Black communities have long used to survive and thrive.

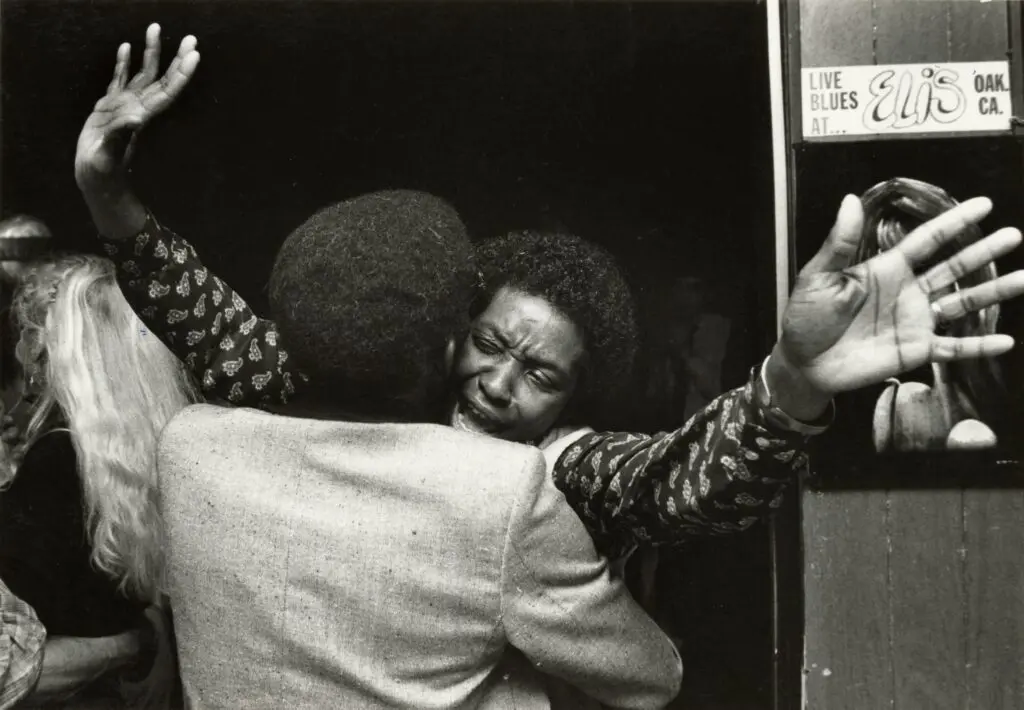

Joy, too, appears in her story as something cultivated rather than inherited.

“I have had to learn joy. It was not an inheritance. It has been a practice—a quest even—and I am still discovering sources. I am finding joy in raising my children to be fully empowered in their Blackness. I am finding joy in the natural world’s beauty and in my spiritual practice. I am the generation in my family that is breaking cycles and that brings me a lot of joy and peace.”

This reflection mirrors a recurring theme in Black Spaces: joy as both resistance and renewal.

When asked about navigating loss and legacy, Candice offers a deeply resonant insight.

“I think Black Americans ARE the tension between loss and legacy. Of course, I feel a deep sense of loss, especially in my own family due to splintered, fractured, and half-told connections and stories. I have been to Africa a dozen times and felt deeply alienated and at home at the same time. That sense of disconnect and placelessness has given me the audacity to claim everywhere as my home. To claim all of those who have struggled for freedom as my ancestors. I have made it my mission to honor my ancestors and ancestors that have impacted the world. Reading their words, listening to their songs, viewing their art, making use of all that they left for us. Keeping their presence alive is a life’s mission for me.”

Her words speak directly to the exhibition’s exploration of place, displacement, and the creative ways Black people maintain cultural continuity despite rupture. As we continue to explore the themes of Black Spaces: Reclaim & Remain, Candice Wicks-Davis’ reflections offer a powerful reminder: reclamation happens in many forms—through art, education, community building, ancestor work, joy, and the ongoing commitment to create spaces where Black life is honored and sustained. Her vision is both grounding and aspirational, inviting us to imagine a future where every Black community has the space to remain, to heal, and to flourish.