Our Museum’s Journey Toward Equity and Anti-Racism: The Leadership of our Staff

In 2020, more than 50 staff members from the Oakland Museum of California (OMCA) actively participated in examining the Museum’s culture and structure and put forth recommendations to move the organization toward becoming a more anti-racist institution. The staff formed into self-designated and self-directed Anti-Racist Design Teams (ADTs) and met intensively over a three-month process that assessed various aspects of the Museum’s programming, working processes, and community engagement, with staff at every level of the organization taking part in the process. OMCA consultants interviewed several members of the Anti-Racist Design Teams in order to document and share this work with other individuals and institutions who are following a similar journey.

This article includes excerpts of interviews with current and former staff participants as well as an overview of the process up to spring 2021. The story focuses on how the teams came to be, the key learnings and recommendations, and the steps we are taking moving forward. The goal of sharing this journey is to ensure OMCA’s continued accountability to its commitment to become a more equitable and anti-racist institution and to encourage others to take on the challenge of making substantive change.

“There are numerous organizations that have appropriated DEIA language, visuals, and narratives to create illusions of justice from which they profit without criticizing their organizational practices, doing any of the actual work, or without being concerned of the harm the charade creates. I didn’t want to be idle if OMCA was to be another perpetrator of this dangerous theme.”

– Carla Forbes, Gallery Guide

“I was inspired by my colleagues, who were so adeptly interrogating the structures of white supremacy at OMCA. They were helping all of us imagine a different way to operate, giving concrete and specific steps toward a different structure, and most pointedly an ultimatum: if we aren’t willing to commit to true anti-racist work then the organization needs to stop outwardly promoting its social justice image.”

– Ryder Diaz, Curator of Natural Sciences

“OMCA prides itself on uplifting underrepresented and marginalized voices, but didn’t have the right relationship internally; the racial uprisings broke open the need to interrogate white supremacy culture from the biggest to the smallest things.”

– Orion Camero, Gallery Guide

“When I started at OMCA a few years ago, we had an all-staff meeting where I looked around and thought ‘wow, this is pretty white.’ I raised my hand and asked “Are there any goals for diversity planning?’ and I felt like everyone just stopped and looked at me.”

– Tayleur Crenshaw, Event Production Assistant

“I was both horrified by the harm others experienced and uplifted by the possibility that we could move forward as a group healing each other and the institution.”

– Catherine Kitz, Event Services Manager

“I started out wanting to save the Museum and now I want to save myself. It takes heart and it’s hard.”

– Nancy Taylor, Administrative Assistant

“We are already seeing the impacts of the ADT work in our current organizational redesign. Does this mean the pain ends and we will become an anti-racist, liberated organization in the next few months? No. Our challenge is too great for that. But we are moving forward in a real way and I believe we really have begun to create the structures to hold ourselves and each other accountable to this work.”

– Christina Young, Associate Director, Visitor Experience

Part 1: A Call to Action

As the Oakland Museum of California remained closed to the public a few months into the pandemic, most staff were sheltering in place at home. The Museum’s Payroll Protection Plan (PPP) loan to fund staff salaries would be expiring in June 2020; OMCA’s leadership team was working on a budget for the upcoming fiscal year beginning July 1, 2020 that could mean reduced hours, furloughs, or layoffs. Tensions and uncertainty were already high, but OMCA staff were pushing forward to figure out how to translate our mission and services into a world where the Oakland community could no longer gather in person. Across the museum field, peers were also struggling with this new financial, emotional, and social reality.

Then on May 25, when George Floyd was murdered by Minneapolis police, what began as a health crisis that expanded into a financial crisis was now emerging as a nationwide reckoning around racial justice. Over the next few weeks, we saw the historically and overwhelmingly white museum field suddenly confronted like no time before in their responsibility to respond to racial injustice in their own communities and within their own institutions. By June 4, OMCA staff were invited to an all-staff Zoom meeting to share personal reactions and responses to the events happening on the streets locally and nationally. More than 100 colleagues attended, many of whom expressed deep pain and anger, not only about national events, but about the disconnect many BIPOC staff felt between their lived experience as employees and the values of diversity and equity that OMCA espoused.

The following week, an OMCA staff member on the event production team, Tayleur Crenshaw, sent an email to the internal employee listserv, which had become a platform for sharing anti-racism resources and supporting protests following George Floyd’s murder. This thoughtful and boldly honest email inspired many on staff with its bravery and its specific calls to action, and is excerpted in part here:

I’m prefacing this email with this in mind: There won’t be a change without complete honesty. I’m sacrificing a lot being a black woman sharing my feelings to an organization that employs me…OMCA talks a lot about diversity. So much so that I think it’s a common idea that we’ve done our due diligence. I enjoy working here but I knew that wasn’t the case even as a visitor before my work. What was odd to me was how much OMCA has always promoted diversity. How much funding comes to OMCA because of its promotion of being a diverse place. How the video on the website that I watched before applying was so much more colorful than a normal day at the museum…

We’ve been talking a lot about what OMCA’s response should be. It’s important that our responses should be actionable. Being more aware, or working towards diversity is not a plan and very hard for employees to track to. Examples of actions could be…

- Flipping the ratio of black artists: white artists (and artists featured online and in the museum). It seems as if diversity comes only in exhibits that revolve around race. Black art does not always have to revolve around pain and suffering and activism.

- Pledging to hire a specific percentage of black people in leadership positions and within the OMCA departments. Especially curators. [Having] no black curators on the team…is crazy for an OAKLAND museum of the ‘people’.

- Opening up the opportunity for Black curators, especially those from Oakland, to host courses, programming and events for free.

With Tayleur’s email at the forefront of many staff member’s reflections, with protesters – including some of our own staff members – engaging in demonstrations or other forms of activism, with increased attention on the Black Lives Matter movement, with the Museum still closed to the public, and with an annual budget due to the Board of Trustees, the OMCA Executive Team launched what they called a “Reboot process.” The idea of the process was that the Museum would need to reboot its priorities within the context of what was emerging as transformational shifts in our health, financial, and societal landscapes. Recognizing the importance of striving to live the Museum’s stated values of inclusion and equity, leadership invited all staff members to participate in an intensive eight-week process of reviewing, reinventing, and refining institutional priorities to center the Museum’s commitment to anti-racism and equity. This would be the first time every staff member at the Museum was invited to participate in assessing, refining and recommending how we would implement institutional priorities. And as important as it was for staff members to be invited into the process, the Executive Team also made efforts to step back from typical hierarchical roles, leaving staff members to self-determine a path forward.

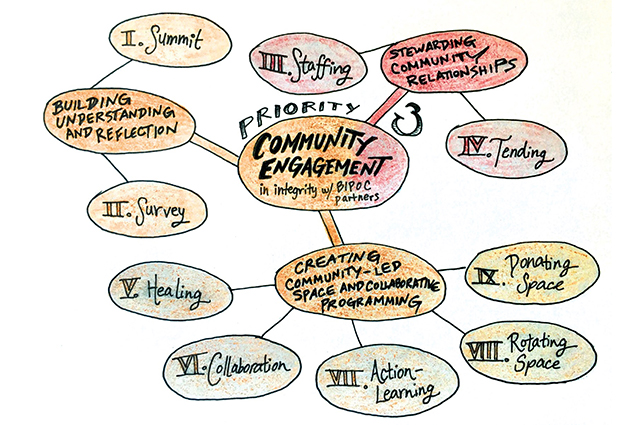

Visual illustrated by Orion Camero, of the Anti-Racism Design Team’s recommendations for community engagement

While participating staff began the process with the charge laid out by the Executive Team, they soon formed into six self-designated Anti-Racism Design Teams focused on core functions of the Museum: collections and programming, fundraising and finance, community engagement, organizational structure and working processes, recruitment and hiring, and over-arching approaches to diversity, equity and inclusion. These teams spent eight intense weeks, alongside their day-to-day jobs, working together to develop priorities and recommendations for the institution.

Imagining and developing recommendations to align all of the Museum’s core functions with anti-racism principles was a task that participating staff embraced, knowing that it would be a heavy lift – both in time and in emotional labor. Staff felt compelled to join in this overwhelming process of reinvention for various reasons, but as expressed by a number of team members, it was some mixture of feeling:

- Frustrated at the disconnect between what the Museum says it values and how those values played out in day-to-day work lives. Many BIPOC staff felt isolated and that their suggested changes were met with resistance or silence.

- Inspired by the moment. Some staff were both concerned by the harm others experienced but uplifted by the possibility of moving forward as a group to heal each other and the institution.

- Jaded by the conversations that were happening across the museum field that have often amounted to a lot of promotional statements, but not much action.

- Eager to speak truth to power, to advocate for making change in concrete and urgent terms, to insist on action and accountability, and to dispel performative gestures.

- Invisible during a pandemic that had relegated OMCA’s most diverse teams away from the frontlines of interacting directly with visitors and instead hidden them behind their computer screens.

- Grateful for colleagues that spoke up articulately, loudly, and bravely for what they believe in and know to be true, even if that also caused some to feel defensive about their role in the situation.

- Fearful that by not joining in this process in leadership roles, the results would be diluted and not address the true magnitude of the issue.

- Responsible for using the power this group has within the institution and within the Oakland community to find solutions to racial injustice, as well as responsible to use whatever power they had to stop the active harm happening to OMCA’s BIPOC staff and communities.

- Capable and called to use expertise in social justice organizing and coalition building to guide colleagues.

- Protective of their own future and that of colleagues, to emphasize what is at stake if this work isn’t done in earnest – not a bad reputation, but a harmful workplace.

Part 2: The Work Unfolds and Lessons Learned

When the Executive Team launched the “Reboot process,” they invited staff participants to make recommendations that would enable OMCA to open the Museum safely, offer visitors a place of healing, and sustain the financial future of the Museum, all with a commitment to equity and anti-racism. With funding from a grant, they also provided facilitation support from Dr. Renato Almanzor, a leadership and equity consultant with whom the Museum had worked with for many years. With funds from the same grant they offered up to 7.5 hours per week of payment for hourly staff and vacation time for salaried staff to honor at least part of the additional work that staff were committing to undertake.

From the very first Zoom meeting with the full group of 50+ staff members from across every department and level of the Museum who opted to take part in this process, it quickly became apparent that the priorities handed down from the Executive Team were too narrow for this collective’s ambitions. The group needed to reinforce that the guiding light would be dismantling white supremacy, thus reframing the process away from a “reboot” and self-designating the “Anti-Racism Design Teams.” Building on some of the recommendations in Tayleur’s seminal email, staff member Carla Forbes led an effort to define priorities around the six areas of core museum work, functions and processes.

The collective created a selection process where BIPOC staff were given first choice of which priority team(s) they wanted to join. The process also aimed to balance tenure at the Museum so that all teams had some members with institutional memory at OMCA. Personal identities were also considered with the intention that each team was as diverse as possible. Within each team, and when the collective met in whole, they drew from the organizing experience and contributions of team member Orion Camero and applied non-hierarchical, community organizing techniques to manage and facilitate meetings and to center the entire group. For every meeting, a time-keeper, a note-taker, and a mood-checker were named. A bike rack/parking lot was used to hold important ideas for discussion at a later date. The “progressive stacking” method was used to queue speakers in open discussions, acknowledging when people wanted to speak and leveling the playing field between staff members who were comfortable and accustomed to speaking and those you might have a more difficult time carving out space for themselves in a large meeting or fast-paced conversation. Staff were urged to be sensitive to power dynamics and to center the voices of BIPOC staff or staff whose perspective can often be marginalized in institution-wide discussions and decision-making.

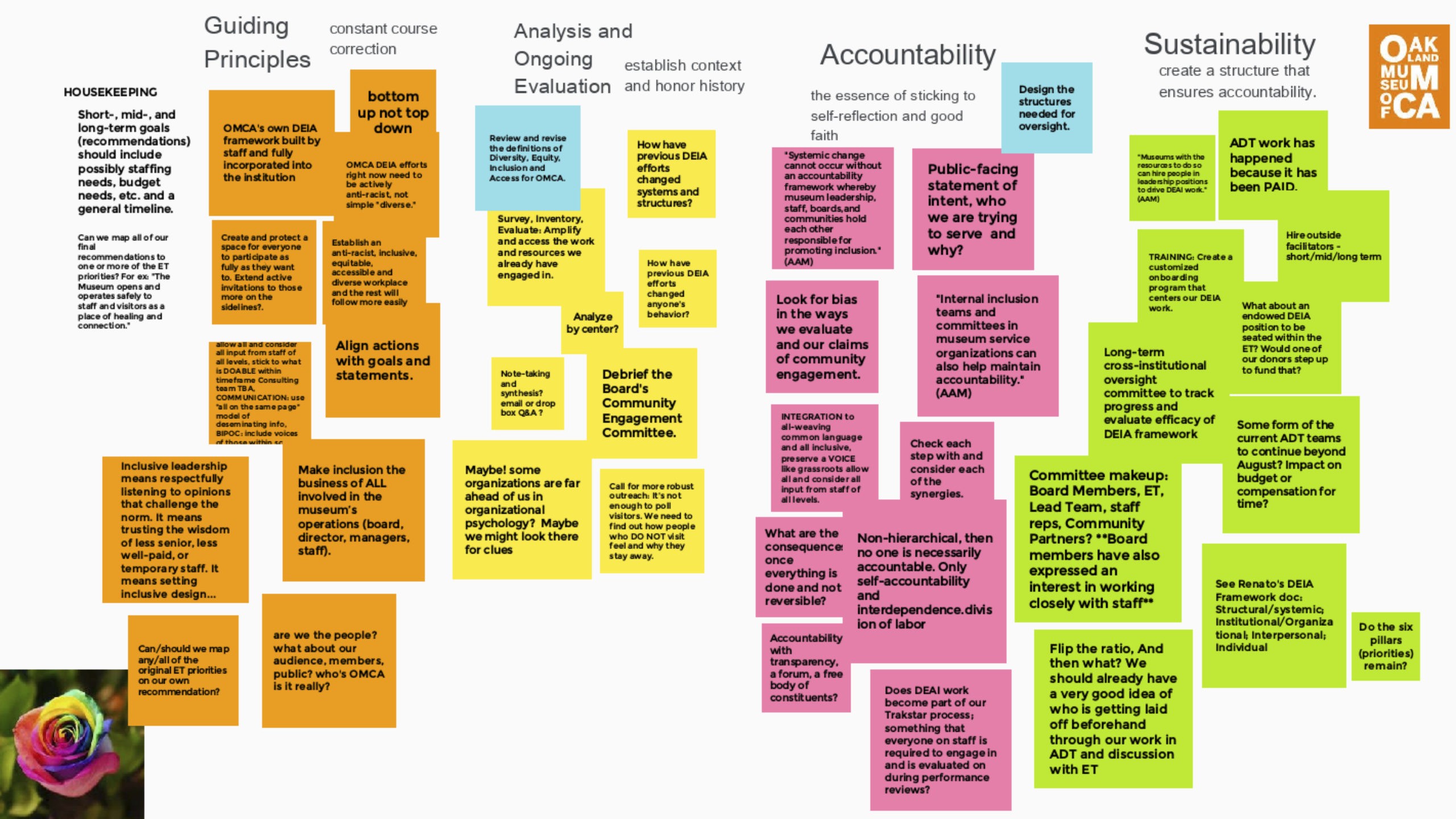

The groups sourced, shared, and explored an enormous range of resources on subject matter from intersectionality to systemic oppression, from distributed leadership to transformative justice, and from community-centric fundraising to pay transparency. They leaned into practices that have served staff well in the past in many other areas of museum work for creatively capturing and evaluating ideas, including Jamboards and mind maps. When possible, teams reviewed historical data and interviewed other staff members about how the Museum had tried to address issues of equity and inclusion in the past, what had worked, and what work remained.

Jamboard for brainstorming of Guiding Principles as the process launched

The process involved a whirlwind of creativity, frustration, and fear and, at the same time was invigorating, reassuring, and inspiring. Because leadership had instituted a specific deadline to receive recommendations in order to inform the annual budget process, ADT participants grappled with incredibly complicated and labor-intensive work at a pace that felt rushed and exhausting. The pressure to communicate criticality and with care, while seizing the moment of what felt like a vital and high-stakes opportunity, was continuously palpable. Along the way, teams worked diligently and industriously to find unique solutions, honoring the timeline that was given for the work while simultaneously resisting white dominant cultural practices of urgency and scarcity. Through this process, the teams learned several things that might translate to other organizations and endeavors:

- In the beginning, take/make the time to build trust among the group members. In a very short period of time, staff had to find entirely new ways of collaborating, break down defensive postures, and discover new faith that change would be possible. Staff members found the ongoing work to be mentally, emotionally, and physically exhausting, and without trust in each other, it would be too easy to not speak up honestly or to simply walk away from a difficult discussion or decision. The defined timeline limited staff’s ability for full trust-building and underscored the need in the future to build time into the process for developing strong working relationships.

- Find ways to take care of yourself and your colleagues throughout the process. Where possible, build in time for care and regeneration into the structure and processes of anti-racism work. Meeting fatigue will set in. You might at times feel disappointed in or outright anger with your colleagues and taking time to constructively work through conflict is also necessary. It’s incredibly difficult to stay energized and imaginative if you’re not working in a sustainable way.

- Think beyond incremental improvements when radical change is required. When an institution has been doing something the same way for a long time, for some people it can feel like even a small step forward is progress. For some of the ADT participants, this moment represented a strategic opportunity for radical transformation, to question every aspect of the organization. Within the context and moment of heightened awareness of institutional and structural racism, this is the moment to join together with colleagues and imagine what a truly anti-racist organization would look like. For BIPOC staff, “the way things have always been” has itself been extreme: an extreme version of inequity, injustice, exclusion, and heterogeneity. White supremacy is insidious and requires constant confrontation against what seems attainable and reasonable at the surface.

- Push yourself in new ways and into new roles. If you’re a white colleague, undertake self-education and come together with other white colleagues to learn, decompress, and recognize your positionality without relying on BIPOC staff to hold that space for you. If you’re a BIPOC colleague, consider the amount of time it takes for the learning curve of your white colleagues as they take time to intentionally and humbly understand the trauma you’ve dealt with throughout your career, life and lineage.

- Leverage the skills and lived experience of your staff. It’s likely that at least some of your staff members have experience with collective organizing and can use this opportunity to grow and be recognized for their leadership. This process revealed how everyone involved brought so much more to the table than job titles might suggest and collectively we hold a plethora of invaluable knowledge.

- Adjust schedules and responsibilities of staff to ensure the full range of voices and ideas are in the room. Unfortunately, many colleagues who wanted to participate in the ADT process were unable to because of the demands of their normal job and/or their home life. The sense of urgency throughout the eight-week process necessitated action, but also disrupted the ability to model the kind of generative, healing working styles that we need to look towards integrating if we want this work to be deep, earnest and sustainable for staff and for the communities we serve. At the same time, the skills, talent and labor of many staff members was revealed through this process, and organizations need to consider opportunities to continue to support staff growth and development beyond a specific Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Access initiative.

- Listen to your colleagues, don’t just wait to speak. This will be an opportunity to connect in a more meaningful, emotionally open way with colleagues who you may be used to working with in only superficial ways before. This work also means that staff members may be heard and understood in new ways where opportunities didn’t previously exist. Practicing deep listening and understanding is at the core of reshaping organizational culture for trust and authentic collaboration.

- Be transparent in acknowledging the gap between where we want to be and what we can actually achieve now, especially during times when ambitions for change collide with financial or other resource constraints. While staff appreciated the resource investment that OMCA made to compensate for participation in the ADT process and the support of consultants, particularly while the Museum was closed, it often didn’t feel enough to offset the intensity of working to counter the traditional frameworks of our dominant capitalist/white supremacist society or to acknowledge the financial benefits that could come the Museum’s way when anti-racist values are implemented. At the completion of the ADT process, OMCA had to recognize its own limitations in its capacity to initiate many of the strategies prioritized by the teams.

- In the end, take the time to decompress and debrief what is bound to be an emotionally difficult and mentally taxing venture or risk extreme burnout. Many staff members underestimated the emotional toll this work would take, especially on contributors of color, all during a global pandemic, financial uncertainty, anxiety about future employment, and the divisive political backdrop that defined 2020. Acknowledge and stay accountable for disparate impact on staff.

- Know that the work is ongoing and never over. It was one thing to be invited to make recommendations on annual priorities and a budget process. It will be another thing entirely to see recommendations take root at OMCA and potentially transform financial, human resources, educational, curatorial, community engagement, and operational practices. OMCA staff and leadership are intent on holding ourselves and our Museum accountable through public communication like this story and in our daily work.

Part 3: Sharing the Recommendations and Moving Forward

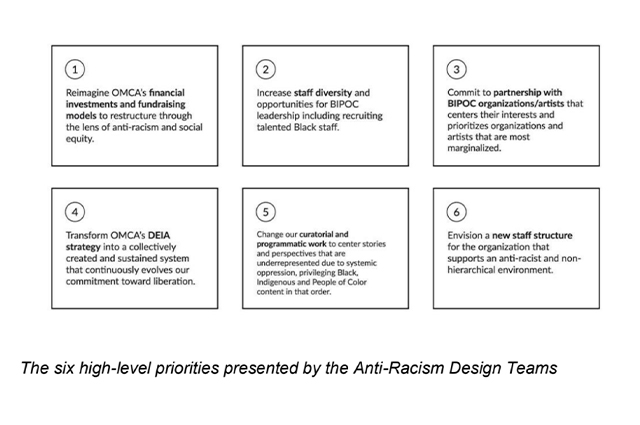

The six high-level priorities presented by the Anti-Racism Design Teams

By the end of the summer of 2020, ADT teams presented six high level priorities supported by some 160 recommendations in short-term actions and long-term strategies, first to the full staff, then to the Executive Team, then the Executive Committee of the Board of Trustees, and finally to the Museum’s Board of Trustees. Those presentations of ADT’s findings and specific proposals for change were another challenging moment to reconcile organizational intention with action. The group of 50+ had been working to develop a shared language and philosophy of operating, but when they presented their recommendations, they were disappointed to find that the organization was right back to working in a hierarchical structure. To the credit of the Executive Team and staff working at OMCA for many years, ADTs also realized that they were making some recommendations that were already in place or in progress that might have been better known if there had been a longer timeframe for the work. To the credit of OMCA’s trustees, they aptly modeled how to grapple with these concepts and examined some of the inherently problematic implications of the role of boards in non-profit cultural institutions.

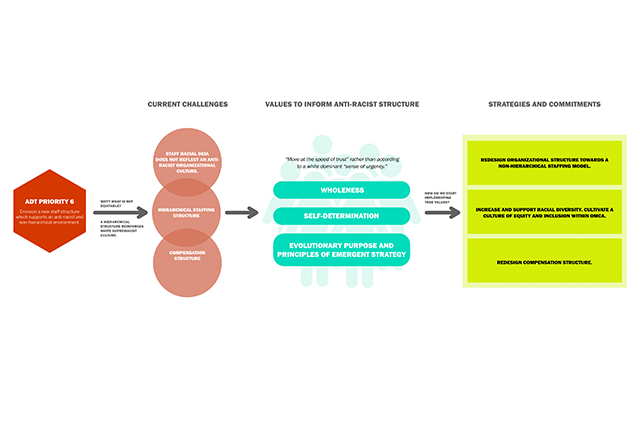

ADT Team #6 created a flow chart focused on transforming organizational structure

Self-selected representatives from the ADTs continued to work with the Executive Team and the Board throughout the fall of 2020 to consolidate recommendations into a shared set of priorities for implementation within the current fiscal year and set the foundation for the fiscal year budget. By the end of November, the Board approved the budget and unanimously affirmed their own Statement of Commitment to Anti-Racism.

Moving into 2021 – with the Museum’s opening pushed back further and anticipated for later in the spring – OMCA leadership shared with the staff that the institution would need to significantly reduce its annual operating budget and personnel costs for what might be several years, even while it invests in new organizational structures and working processes. This organizational redesign process, which will be described in a separate article, was strongly informed by the recommendations and ADTs and built on the collaborative and transformative equity-based work of OMCA staff.

While many approached this next phase of OMCA’s journey with nervousness and skepticism, staff members are holding out hope that OMCA as an institution will fundamentally change. ADT members have expressed the hope that their ideas are seeds that the organization will fertilize and collectively tend to year over year. Staff are calling on the organization to continue this hard work, and leave space for anger and sorrow and healing while also staying grounded in our values, and unified around our vision. OMCA’s vision is to extract white supremacy from the organization and to become a more inclusive, less hierarchical and more collaborative workplace, where people are valued for their talents, not their job titles, and where everyone has a seat at the table.

Looking into the precarious future of the museum field, OMCA staff encourage our peers to dispose of excuses for upholding, defending or justifying violent infrastructures of whiteness and finally accept the changes necessary to address the harm of staff members within these institutions and to fully serve the diverse populations of visitors, staff, and community members who have been historically marginalized. When institutions realize the threat to their own relevance and wellbeing for all by upholding racist practices, then committing to foundational anti-racism is a critical priority. If institutions believe that racism is a problem and one with which museums have been historically complicit, then anti-racism must be a priority.

The story of OMCA’s Anti-Racism Design Teams is not a story about a shining ability to “do equity work,” but instead about normalizing processes that are amorphous, imperfect, and ever shifting, and yet remain rooted in clear objectives and shared principles. OMCA’s story should be just one of many examples of how it’s possible to create tangible and decentralized efforts in response to racial injustice, led by, for, and with a community of dedicated staff.

Following the ADT process, the Oakland Museum of California undertook a major organizational redesign that strived to center anti-racism as a core value and principle even as the restructuring required reduction of approximately 20 positions or 15% of the workforce due to the financial ramifications of COVID-19 and 15 months of closure. The Museum is currently implementing the new structure and beginning to move forward on recommendations from the Anti-Racist Design Teams. The work is ongoing and OMCA will continue to share the story of its journey from multiple perspectives of staff members, leadership, and community.